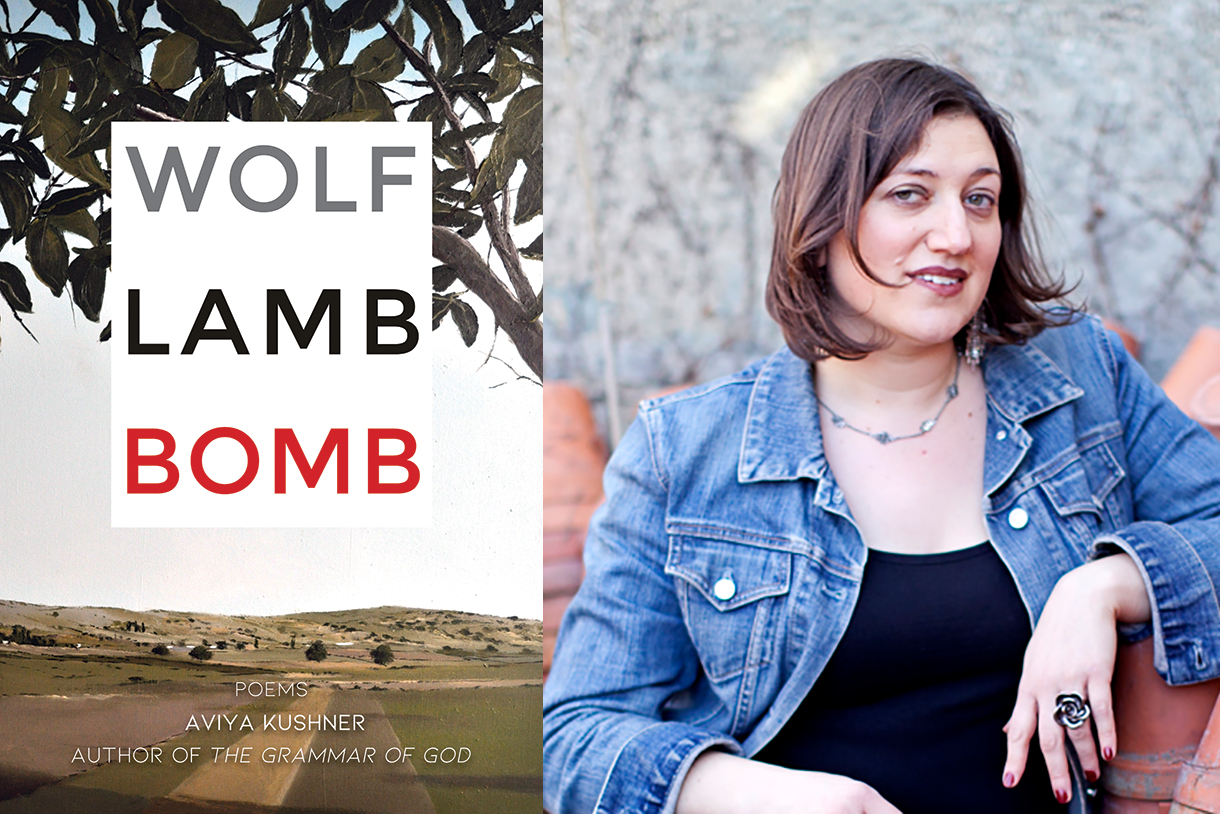

Associate Professor Aviya Kushner on her NEA Fellowship, winning Best Poetry Book for WOLF LAMB BOMB

Associate Professor Aviya Kushner has always been fascinated by language and how it shapes us all. After first reading William Faulkner short story, “Dry September,” she realized that she wanted to learn how to tell stories, specifically stories that could be interpreted differently after each reading.

The past year has been a whirlwind of for Kushner, beginning in June of 2021, when her poetry collection WOLF LAMB BOMB was published by Orison Books. The book’s concept was created when Kushner’s editor asked her about a reference she made in her previous work, The Grammar of God, to the Isaiah poems. Kushner began writing the Isaiah poems in her twenties and continued for 20 years following. During that time, the collection evolved into what Kushner calls a reimagining of Isaiah in our contemporary era of violence, political conflict, and hatred.

Then, in December, WOLF LAMB BOMB won the 2021 Chicago Review of Books Award for Best Poetry.

Stunned and moved to receive this recognition, Kushner expressed deep gratitude at the award ceremony (and despite forgetting all finalists had been required to prepare a speech, she said she thankfully remembered to thank her parents, who were in attendance). “The CHIRB is special because it is given by Chicago book critics and Chicago bookstore folks, so it is recognition from this city's fantastic and diverse literary community.”

Still riding the high of the CHIRB Awards, Kushner was selected this past January by the National Endowment for the Arts, along with 23 other translators, to translate works from 16 languages and 18 countries into English. With this fellowship, Kushner will support the translation from the Hebrew of selected poetry written by Tel Aviv-born poet Yudit Shahar.

“I started translating Yudit Shahar’s poems after the director of a translation institute called me again and again, insisting that I had to read Shahar’s work,” she said. Kushner quickly realized Shahar’s work was a perfect fit – this was poetry she had both loved and needed.

“It was by a woman and a rebel, someone who shared some biographical details with me—we had both grown up in religious homes and fought hard for a life in poetry,” she said. “Shahar wrote about economic inequality, and I had started my career in financial journalism; I knew just how much money mattered. When I finally met Shahar, I realized that we communed.”

The fellowship will be centered on Shahar's three award-winning collections of poetry: It's Me Speaking (2009), A Mad Woman on Every Street (2013), and Holy Illusion (2021)—all of which tackle economic injustice. Kushner has already completed the first collection and has placed more than two dozen translations in literary magazines. She now plans to complete the translation of those latter collections, put the finishing touches on a critical introduction, and make selections for the Selected Poems.

Kushner’s life has widened through friendships with the writers she translates and through deep connections with other translators all over the world. “Working on these translations in cafes on two continents, reading and rereading the Hebrew and trying to make poems in English out of poems in Hebrew, I realized that I have two creative lives—and that my happiest moments live in the space between languages,” she told the National Endowment for the Arts.

She discusses the beginnings of her latest poetry collection, inspiration for her work, and how she continues to learn from her own teachings in the classroom:

What drove you to this point in your life? When did you know you wanted to become a writer?

I grew up in a Hebrew-speaking home, and I have always been fascinated by language and how it shapes us all.

I have also been interested in stories for as long as I can remember, in all their many forms. When I was a sophomore in college, I took a fiction class and we read a short story by William Faulkner called “Dry September.” Every time I read that story, I thought something else happened.

I remember thinking—"I want to learn how to do that.” I had no idea what I was taking on.

I wanted to learn how to make a readers see the world in multiple ways, and how to get readers to question their own assumptions. I’m still learning how to do that, in both poetry and prose.

What inspired you to write WOLF LAMB BOMB, is this topic personal for you?

When my grandfather died, I realized that there was nothing for a grandchild to do in Jewish tradition. A child of the deceased sits shiva and says kaddish, but a granddaughter? Nothing.

So I made up my own ritual.

I decided to go to synagogue, early in the morning, each Shabbat for a year. My grandfather, a German Jew, was very punctual—but getting up early is not one of my personal strengths. That year in synagogue gave me the opportunity to read the entire Torah again, as an adult.

I was in my early twenties at the time. Because I was finishing a graduate degree in poetry, I was thinking in poetry terms. I was completely wowed by Isaiah as a poet, and I started writing poems in response—talking back to Isaiah.

In time, Isaiah became my education, my guide in poetry.

I had no idea I would keep doing this as I slowly became a writer. I wrote these poems as a reporter in Jerusalem, as a young woman in post-9/11 New York, in graduate school in Iowa, and then in Chicago, where I began teaching at Columbia. In times of violence, terror, and political unrest, I found myself returning to Isaiah, who suddenly felt very contemporary. Isaiah is concerned with justice, and he details violence and its effects.

I was also intrigued by how Isaiah had the ability to make anger seem beautiful, when in regular life, anger is often depicted as something ugly. I thought a lot about who has the right to be angry in our society and why.

How has your experience at Columbia help you write and finish your book?

Something I notice while teaching is how important the structure of a book is. When the structure is deeply right, students can feel it. I spent a lot of time in the final stages of WOLF LAMB BOMB on poem order—in other words, structure. I wanted the title, the section titles, the table of contents, and the cover to all fit together into one whole.

What advice do you have for current and prospective students?

Follow your dreams. The most important thing is to continue.

I received wonderful advice from one of my professors. “I cannot tell you how kind the world will be,” he said. And I think about that a lot; “how kind the world will be” – what other people think of your work – is not in your control, but continuing to write, continuing to make art, is in your control. It’s a decision and a commitment.

Working hard to continue, and keeping the commitment to write, Kushner is excited for every opportunity to share these translations with the world.

“This fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts will allow me to speak those words and not whisper them,” she said. “It will let Shahar’s passionate cry for economic justice be heard.”

She says now is the time to reconsider prophetic language and ask what this ancient poetic example can contribute to our society. “To me, it’s not just about religion—it’s about thinking about the world as it is, and the world as it should be,” she said. “At this fraught moment in history, all of us are considering what the world actually is, and what it could and should be. That is prophetic terrain. And that is also the space of poetry.”

Recent News

- Columbia Holds Sixth Annual Hip-Hop Festival

- 5 Questions with Columbia Alum and Trustee Staci R. Collins Jackson

- Anchor and Reporter Paige Barnes ’21 Found Stories Worth Telling at Columbia

- Make Columbia Part of Your Holiday Season: Watch Alum Movies and Shows

- Fashion Design Alum Shaquita Reed ’18 Expresses Herself Using Different Mediums