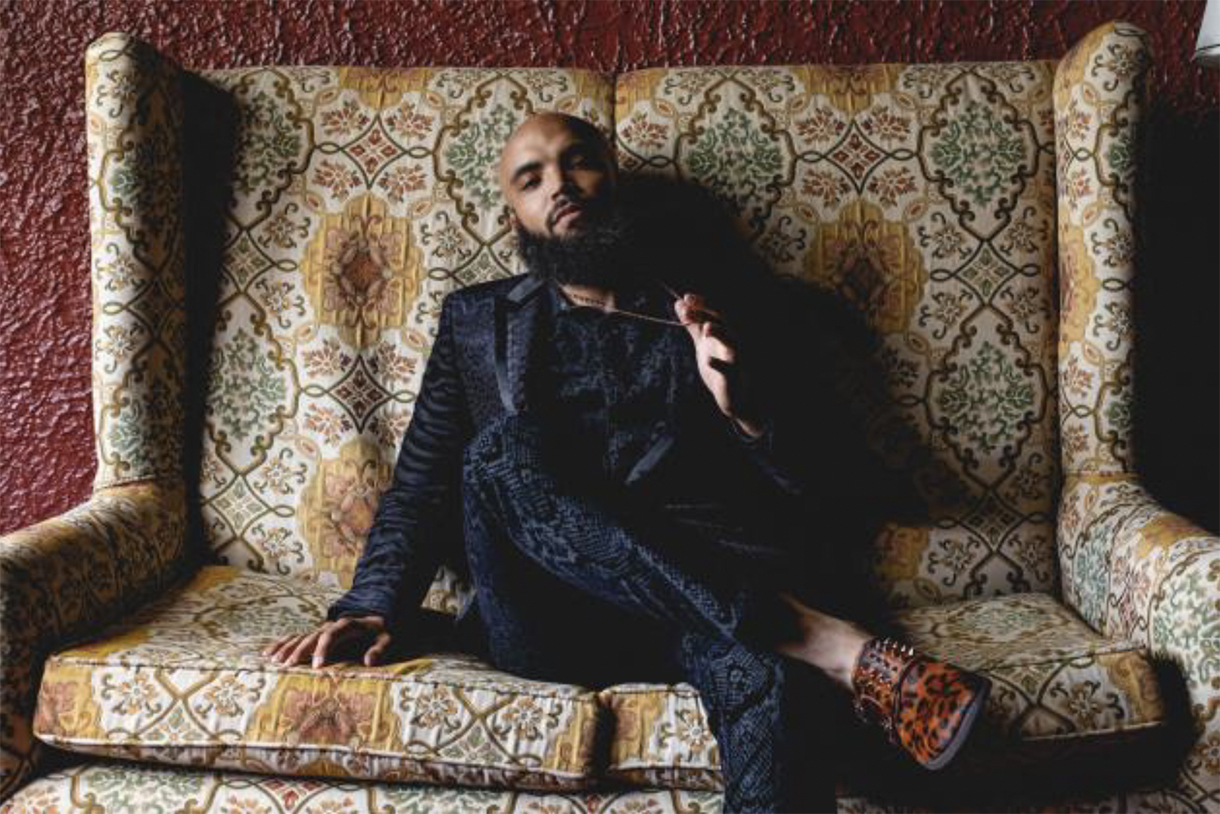

Marcus Norris BMus ’14 on Composing, Breaking Barriers, and the Next Steps Forward

When Marcus Norris was growing up in Jackson, Michigan, he was surrounded by music. He had two uncles, who he describes as “legends,” who were in the world of producing and rap. His mother introduced him to Mary J. Blige. And he spent much of his free time listening to G-Funk, Dr. Dre, George Clinton, and Tupac. By the time he was 13, he was writing his own music, privately. “When I first started, I didn’t even show it to anybody,” Norris says. “It was just for me.”

His instrumental compositions and arrangements helped him process his life. In fact, Norris describes the cathartic effect of his music as an experience akin to journaling. But slowly, over time, it became clear that his music was going to be more than a private experience—it was his path forward in life.

When it came time to choose a college, Norris, who has never been afraid of leading from the heart—went to the school that promised an excellent education in the center of Chicago. “What attracted me to Columbia was I fell in love with Chicago, the city, and Columbia is right in the middle of it,” he says. He found the music school to be refreshingly modern and set up for people who wanted to chart their own unique course in their careers. “I think [the music program] lends itself well to people who aren't trying to follow maybe the traditional path or are into fusing things the way I am,” he says.

Throughout college, Norris absorbed the expertise of the mentors around him. He can list them off almost stream-of-consciousness now, years after he’s graduated: Sebastian Huydts (Chair), Donald Neale, Ilya Levinson, Michael Cunningham. Cunningham, in particular, had a positive impact on Norris. “He was an arranger and composer, and he let me come to my first studio sessions for string orchestras and stuff,” Norris says. “I would help him and copy his parts and do all the little tedious stuff, but I didn’t realize that I was absorbing a lot of it.”

Despite building a rich and robust community and having a dedication to his creative practice, Norris faced challenges that were part and parcel of a society rife with systemic racism. “I feel like the most challenging part [of being a musician and composer] is being a Black man in a world and a space that was made…it was designed to exclude you; you know what I mean? It can be pretty exhausting to be in these places.” As Norris points out, it isn’t only that racism and exclusionary tactics have resulted in so few people of color in the world of composing, but “it’s that that doesn’t bother anybody. That they don’t notice.”

Norris counters this taxing reality by doubling down on his efforts to build a supportive community that serves established artists, listeners, and up-and-comers. In fact, in starting Los Angeles’ South Side Symphony, Norris embraced the motto “Our music and our time.” He recalls, “I started with, like, ‘Okay, what if the orchestra didn't exist, but it was invented now, this year, by a young Black man in his twenties. What would that look like? What would it sound like? What would they play? Where would they play?’” The result has been a transformative ensemble playing in unique places. The only ensemble, Norris has previously stated, that would play “Back That Thang Up” and Beethoven in the same set.

Now, earning his Ph.D. at UCLA, Norris has yet another accolade to add to his list of accomplishments. He has recently been chosen as one of three composers for the Chicago Philharmonic Inaugural Residency Program for composers of color. It’s an experience that Norris hopes will allow him to reach even more people. As he says, “I'm just a lover of music and art, and I just want to make something that's really powerful and touches people, that speaks to people like me, with shared life experience, but also people who don't. Maybe they can still appreciate it. I just want to make something that means a lot to me and people like me.”

And to others who might want to follow in his footsteps Norris advises, “I would say just lean hard into your quirks and your interests… I'm learning those things make you unique and it kind of becomes your calling card.”

Recent News

- Columbia Holds Sixth Annual Hip-Hop Festival

- 5 Questions with Columbia Alum and Trustee Staci R. Collins Jackson

- Anchor and Reporter Paige Barnes ’21 Found Stories Worth Telling at Columbia

- Make Columbia Part of Your Holiday Season: Watch Alum Movies and Shows

- Fashion Design Alum Shaquita Reed ’18 Expresses Herself Using Different Mediums