Raising Hearing Awareness Among Future Sound Professionals

Benj Kanters' class on hearing at Columbia offers future sound engineers the knowledge to protect themselves and those around them from the dangers of excessively loud sound. Inspired by his class, some students have gone on to become audiologists.

Benj Kanters' class on hearing at Columbia offers future sound engineers the knowledge to protect themselves and those around them from the dangers of excessively loud sound. Inspired by his class, some students have gone on to become audiologists.The ability to recognize the nuances of sound is essential for anyone who records, processes, or mixes audio—in the studio, for live performances, or for cinema and games. “It’s one of the most important tools in any sound engineer’s toolbox,” says Benj Kanters, soon-to-be retired associate professor in Audio Arts and Acoustics (AAA) at Columbia College Chicago who worked for decades as a professional sound engineer.

“How do I know a microphone sounds any good if my ears aren't working right?”

Sound engineers—and many of the musicians and producers with whom they collaborate—rely on their hearing to produce quality sound. Yet, their profession often puts them at risk for hearing loss, with long durations of exposure to loud sound increasing the likelihood of hearing damage.

That’s why Kanters, once a concert and studio sound engineer, has dedicated much of his academic life to raising awareness about hearing and hearing conservation among AAA students at Columbia. His class on hearing at Columbia offers future sound engineers the knowledge to protect themselves and those around them from the dangers of excessively loud sound. It has also introduced students to a career trajectory they may not have initially foreseen. Inspired by his class and classes in perception and cognition and equipped with the unique skill set an AAA degree provides, several of Kanters’ students have gone on to become audiologists—health care professionals who identify, assess, and manage their patients’ hearing disorders.

Kanters’ passion for education developed following a long and successful career as a sound engineer and business owner. In the 1970s, he ran sound as a partner at Amazingrace—an influential and popular performance venue in Evanston—and in the 1980s, was a partner and engineer at Studiomedia Recording Company, also in Evanston.

Thanks to an opportunity to develop and teach audio classes on the side at his alma mater Northwestern University (NU), he found his way to academia and, eventually, to Columbia. Here since the 1990s, Kanters helped build Columbia’s current Audio Arts and Acoustics department into what it is today. “I was kind of the first real hire to the new sound program,” he says.

A class on hearing physiology, which he took in 2000 while earning his master’s degree sparked Kanter’s passion for hearing awareness thanks to Professor Jon Siegel in the NU Communication Science Department. “It was the most exciting course I've ever taken in my entire college career,” Kanters says. “Here I was learning about human physiology, but in a language that I already knew as a sound engineer.”

Add to that a growing relationship with local audiologist, Michael Santucci, who Kanters describes as “the audiologist to the stars” because of Santucci’s work with musicians in his clinic Sensaphonics. (Kanters suggests checking out the client page.)

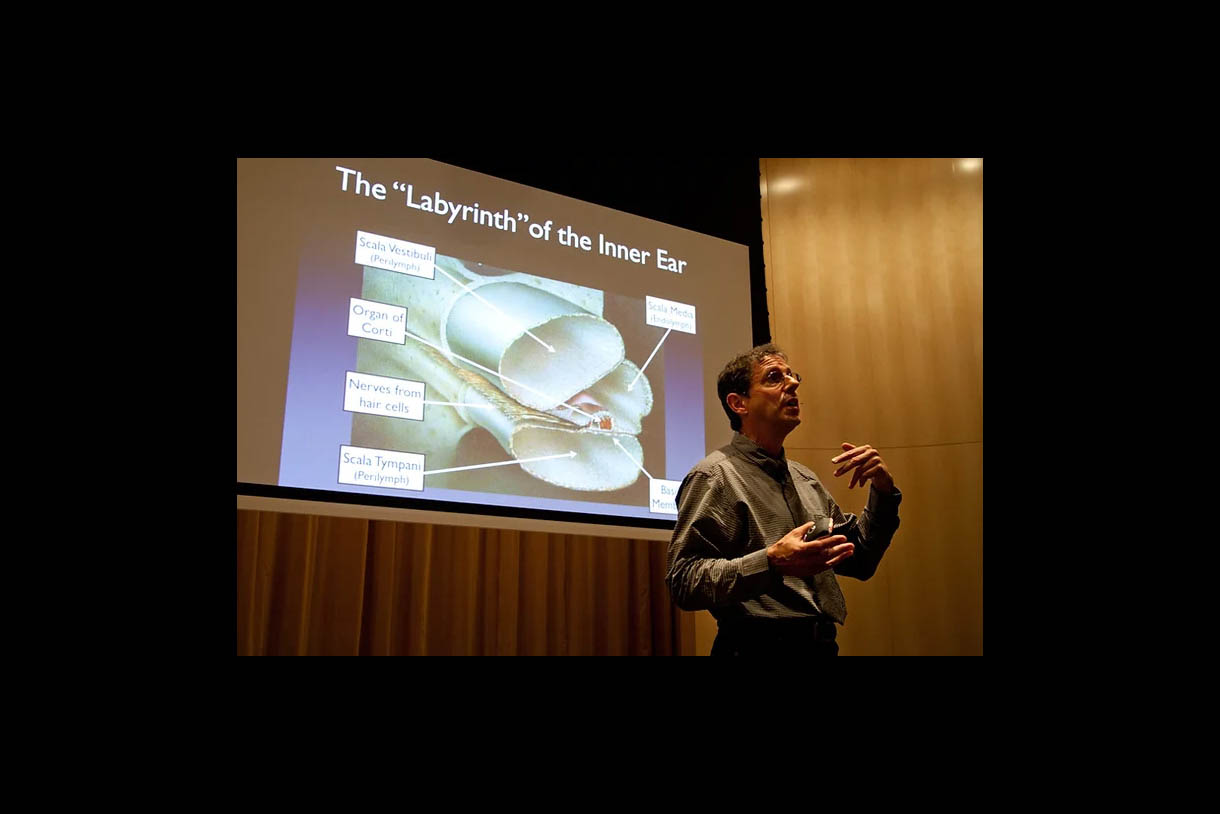

These experiences resonated deeply for Kanters and inspired him to create and teach what is now a required course for Columbia AAA students: "Studies in Hearing." The class introduces students to the fundamentals of hearing physiology and issues related to hearing loss and disorders.

“Once I teach how the ear works, I can show how the ear is injured—from a sound engineer's perspective—to help students understand what's actually happening,” he says. “I can describe it to audio students in terms and terminologies that they can understand, because it's audio; this is audio biology. I help them answer the questions, what does the damage sound like? Where are the hazards? How do I assess those hazards? What are the conservation technologies available to me?”

Educating future sound engineers on these topics is important for their own well-being as well as for those around them. They are professionally well-positioned to make a difference, Kanter says. “Sound engineers are at the center, taking care of the musicians and taking care of the audience. And with evolving audio technology, they are capable of delivering really high-quality sound at relatively safe levels.”

This spring Kanters will retire from his full-time responsibilities at Columbia, but he will remain as part of the adjunct faculty and continue to teach "Studies in Hearing" at Columbia. He’ll also continue his work with the nonprofit he founded called HearTomorrow, which promotes awareness of noise and music-induced hearing loss through workshops he leads for students and professionals in audio, acoustics, and audiology.

“This topic is endlessly fascinating to me,” he says. “I've been teaching this class now for 20 years, and I still love teaching it because there are always new discoveries and technologies to add to the course curriculum.”

MEDIA INQUIRIES

Jill Waite Goldberg

Communications Manager

jgoldberg@colum.edu

312-369-7054

Recent News

- Columbia Holds Sixth Annual Hip-Hop Festival

- 5 Questions with Columbia Alum and Trustee Staci R. Collins Jackson

- Anchor and Reporter Paige Barnes ’21 Found Stories Worth Telling at Columbia

- Make Columbia Part of Your Holiday Season: Watch Alum Movies and Shows

- Fashion Design Alum Shaquita Reed ’18 Expresses Herself Using Different Mediums