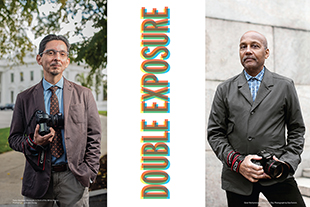

Double Exposure

DEMO Feature

Two Pulitzer Prize-winning photographers reflect on their careers and the craft of photojournalism.

As photojournalists for The New York Times and The Associated Press, Pulitzer Prize-winning photographers Ozier Muhammad ’72 and Pablo Martínez Monsiváis ’94 have watched history unfold right before their eyes.

In his 30-plus year career, which included 22 years at the Times, Muhammad covered everything from the war in Iraq to the Obama campaign, the Haitian earthquake, and the state funeral of Nelson Mandela. In his 19 years at the AP, Martínez Monsiváis has trained his lens on four presidents and is still on the White House beat today.

Here, DEMO talks with these two Columbia College Chicago grads about their prolific careers, changing (and often wrangling) technology, and an ever-shifting media landscape.

DEMO: You’ve both been working at the highest levels of photojournalism for decades. But you each won the Pulitzer Prize relatively early in your careers. Ozier, your 1985 award was for work you did at Newsday.

MUHAMMAD: It was about the famine in Africa, an international reporting prize. I shared it with Josh Friedman and Dennis Bell. The assignment from the foreign desk was to cover the 10th anniversary of the first big famine of 1974. We ended up in Ethiopia and we just happened to be there when the situation was at its worst. We dispatched stories from there for a couple of months. I had to ship [film] by DHL courier ... you know, it was prehistoric times. If you didn’t have an AP device...

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: A transmitter. Over the phone lines.

MUHAMMAD: I didn’t have one, so I had to ship [the film] back. When the first dispatch was published, it seemed to stir a hornet’s nest with the rest of the media and also the U.S. and European governments. Because we were so early on that story—that’s why it won the prize.

Ozier Muhammad, Newsday, 1984—This photo from Ethiopia was part of the "Africa The Desperate Continent" series that won the Pulitzer Prize for International Reporting in 1985.

DEMO: Pablo, your AP team won the 1999 Feature Photography prize for its coverage of President Clinton’s impeachment. What was that like?

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: Until that point, I hadn’t paid attention to how intense the impeachment was. It was madness. They threw me into a hornet’s nest, and I had literally no idea what was going on. I told people later: You cannot send people blindly into events like this anymore. It’s incredibly competitive here in D.C., for like, inches, for the same photo. But the photo that was entered [for the Pulitzer] was taken my second day on the job.

DEMO: That’s the photo of U.S. Representative Bob Livingston and former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich walking down the steps of the Capitol?

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: Yes. I was shadowing the chief photographer for the AP, and they sent me to the Hill to photograph this event. I brought the photo back and they were like, “Hey, this is a nice photo,” but I didn’t realize it was entered as part of the Pulitzer package. When I heard we won, I was at Jiffy Lube. They gave me a call, and I thought it was a joke, but they were like, “No, you’ve got to come back down to the office.”

The whole time, I thought the impeachment was going to be the craziest thing I’d ever seen. No. It just keeps getting nuttier and more intense. But it turns out that I really like political coverage. And every now and then, they still send me to cover sports.

DEMO: What have been some of the most memorable moments you’ve had on assignment?

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: The means by which we do everything now is speeding up. During the week of the [2016] election, we hear last minute that the president-elect is coming [to the White House] on Thursday to meet Obama. I needed to transmit electronically straight from the Oval Office, which I hadn’t done yet. I had not practiced this whole setup—also, there’s radio frequency blockers throughout the West Wing. I’m not 100 percent sure it’s going to work.

I get to the Oval Office, take my spot in the middle, and literally, it’s the first time I’ve actually looked at Donald Trump. I hadn’t covered any of the election. I’m like, “Oh my God, it’s the guy from The Apprentice. I can’t believe this is happening.”

You want the photo of them shaking hands. President Obama speaks, and then he offers his handshake, and I take the picture ... and my camera blinks with a green light. That means it’s transmitting. I’m like, “Yesss, it’s going, it’s going!” The whole thing was so surreal.

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, Associated Press, 2016—President Barack Obama and President-elect Donald Trump shake hands during their first meeting in the oval office.

DEMO: Ozier, you must have a few “can’t-believe-that-happened” stories.

MUHAMMAD: Oh yeah, there are a few. In 2013, during my waning days at the Times, Nelson Mandela was in the hospital and I was going back and forth between Johannesburg and Pretoria on what we called the “death watch,” to be quite frank. Mandela happened to hold on for several months, but I was there for only one—during his birthday celebration. I went to a Catholic school in Soweto where I photographed children singing songs in tribute. I went to the African National Congress [ANC] office and a few other places. We were nine hours ahead of New York. When I got back to the hotel, I transmitted everything. It was probably almost 1 a.m. when I got it all done. Just as I was about to hit the sack, I get a call from the Times’ foreign desk, asking me to fly to Cape Town immediately for a Saturday profile on Ahmed Kathrada, one of the ANC leaders who had been in prison with Mandela.

I was dead tired. Plus you’re driving on the opposite side of the road, and the steering wheel is in the passenger seat, right? I thought, “Now how the hell am I going to get to Cape Town?” I had to transmit the pictures by 8 a.m. South Africa time so that they could make the Saturday paper. I managed to fly in and photograph Kathrada...Then I had to transmit the pictures. It was the first time I used a dongle—basically, a thumb drive with a transmitter in it. I gave it a try, but I just couldn’t connect. I drove a little distance away and I still couldn’t connect. Turns out, it was just that I was so whacked out with fatigue—it was some protocol I didn’t quite hit. I didn’t have my TCP/IP settings right, but I finally figured that out and it made the paper. But it was pretty dicey for sure.

DEMO: There have been so many changes in technology, culture, and media platforms over the years you’ve both been working. How do you stay centered?

MUHAMMAD: People are more prickly, even hostile, about being photographed in the public sphere. In recent years I’ve kept a copy of the Constitution in my back pocket. I pull it out whenever a cop tells me I’m infringing or that I have to pay someone for their photograph. I’ve said a number of times: When I photographed President Obama, do you think I slipped him a $20 every time? No, that’s not what happens. We do have certain rights.

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: If I learned anything from art school, it’s that you’ve got to evolve ... the tools are always changing.

Ozier Muhammad, The New York Times, 1994—Presidential candidate Nelson Mandela appears in the National Soccer Stadium as he campaigns for the presidency of South Africa in Soweto.

DEMO: What worries you in this era of “fake news?”

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: When Ozier took his photos in Africa, he was [directly] showing us the work [through verified sources]. Now we’re seeing images from everyone [on social media]. What scares me is that somebody can falsify imagery and people take it for the God’s honest truth. People steal images and use them for their own agenda. They’re not with the AP or the Times. They’re Joe Schmo, but with access to the same ways of disseminating information. I’m no longer just competing with Reuters, I’m competing with a guy with a smartphone. It’s crazy. Accountability is gone. When a photo has the stamp of the AP, there’s a lot of weight to it. But some people don’t understand that.

DEMO: Is smartphone culture contributing to public mistrust?

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: This past summer I went to Zimbabwe, which is very restrictive. The only way people know the news is by talking with each other via social apps. When the establishment is not letting anybody know what is in the best interest of the people, Snapchat, Facebook, and Instagram are fantastic. It’s a perfect example of when it works well.

Here, we have the reverse. During the last election, people literally segmented what they wanted to hear. I don’t know if we can find an even ground. But it’s always been the case—like with newspaper barons. At the turn of the [20th] century, they pushed us into the Spanish-American War to push newspaper sales.

I think you can argue both sides. Being aware, knowing the limitations of the tools and what they’re capable of doing, is the priority.

MUHAMMAD: I think we’re living in a great period, for many of the same reasons that Pablo articulated. We have all kinds of means of gaining information through social media platforms. I don’t think we have to worry too much about propagandizing when it comes to the mainstream media, like the wire services, the Washington Post, or The New York Times. Their ethics are clear and their staffs are very mindful of abiding by the rules. But one of the things that concerns me is what [influential journalist] Walter Lippmann called “manufacturing consent” about a hundred years ago. This applies mostly to text, the stories that are written—false equivocations and things of that sort, which is where most of the [current] hostility comes from. It doesn’t have as much to do with the medium of photojournalism.

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, Associated Press, 2016—Barack and Michelle Obama watch the musical performances at the 2016 National Christmas Tree lighting ceremony near the White House.

DEMO: What might surprise people about your work?

MUHAMMAD: The drudgery ... long waits and early setups. No matter the weather, you must get in place for a highly secured outdoor event upwards of 12 hours beforehand. Also, there are seemingly interminable stakeouts that may not yield anything. I had to wait outside Bernie Madoff’s Upper East Side apartment starting at 6 a.m., until he was to appear for sentencing at a courthouse in lower Manhattan in the afternoon. I never saw him. Madoff might have stayed in a hotel the night before he was sentenced.

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: The White House beat is very competitive and D.C. is stacked with talented photojournalists. If you blink, you will get your clock cleaned. Add deadline and work pressures—but surprisingly, everyone is very professional. None of my competitors are spiteful or malicious. We all tend to look after each other and help each other out. People outside of D.C. frequently comment about how well we all get along and how unusual this is, given what we do and what is at stake.

DEMO: Any advice for aspiring photojournalists?

MARTÍNEZ MONSIVÁIS: As a photojournalist, you have content that you need to advertise, distribute, and invoice for. Don’t give anything away for free, especially to another entity that will profit from your hard work. Journalism is a business, and as a photojournalist you have to look at it as one. Also, be—and stay—humble, no matter what you do and how many awards you accumulate throughout your career. This is the only thing people will remember. One of our jobs as photojournalists is to be human. When you get assigned “tragic” events, such as hurricanes or earthquakes, you will be seeing people at the weakest point in their lives. Don’t abuse that. Don’t be an emotionless robot with a camera taking photographs of people because you want to win Picture of the Year.

MUHAMMAD: Learn how to shoot, capture, and edit video and sound. Sharpen your writing and interviewing skills. Learn how to gather information. Staff jobs are disappearing— photojournalists of the future will be free agents. Be willing to relocate.

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, Associated Press, 2016—The Air Force Thunderbirds fly overhead as graduating cadets celebrate at the U.S. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, Associated Press, 2017—President Donald Trump at his desk during his first flight on Air Force One.

Pablo Martínez Monsiváis, Associated Press, 2009—President Barack Obama, center, salutes an Army carry team during a dignified transfer ceremony at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware.

Ozier Muhammad

Ozier Muhammad, The New York Times, 1999–Supporters of Olu Falae, the candidate for president of Nigeria, outside of his home.

Ozier Muhammad, The New York Times, 2012—NATO members dined at the Art Institute of Chicago while an Occupy Wall Street protest took place outside on Michigan Avenue.

Ozier Muhammad, The New York Times, 2016—A marcher in the New York City Gay Pride Parade wears an ORL sticker to memorialize the deadly shooting at Orlando nightclub Pulse.

Ozier Muhammad, The New York Times, 2011—Occupy Wall Street protesters circle the New York Stock Exchange without incident.