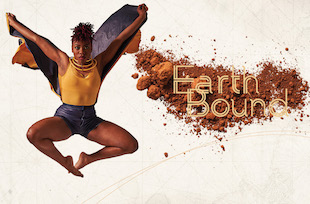

Earth Bound

DEMO Feature

The TransAtlantic Project—led by Vershawn Sanders-Ward ’02—brings Chicago’s Red Clay Dance and Uganda’s Keiga Dance Company together at the Dance Center.

Dance, by its very nature, is transformative. Bodies morph, curve, undulate, and writhe in rhythmic motion. But dance at its most primal is more than just meticulous and memorized choreography. It can work as connective tissue between the past and present, move beyond the boundaries of culture, and bring people together on a foundational, primordial level.

That’s the mission behind Red Clay Dance, a Chicago-based dance troupe focused on invoking change on a local and global level through performing and teaching the dances of the African diaspora—or, people of African origin who have dispersed to other off-continent communities but still contribute to its cultural development. Founded in 2008 by movement artist Vershawn Sanders-Ward ’02, Red Clay Dance has spent the last 10 years cultivating a unique space in the Chicago dance scene.

This year, it will complete its most exciting endeavor yet: the TransAtlantic Project, a year-long cultural exchange with choreographer Jonas Byaruhanga and the Keiga Dance Company from Kampala, Uganda. Their collaborative performance, EKILI MUNDA|What Lies Within, will premiere at the Dance Center at Columbia College Chicago this November 8–10.

It’s an incredible evolution for Red Clay Dance, and for Sanders-Ward, whose vision both sharpened and expanded after decades of training, traveling, and education.

A Visionary is Born

Sanders-Ward started dancing at a young age, around 6 or 7. She took a break in high school to play sports like softball, but missed the role dance played in her life. She eventually got back into it, and went on to attend Columbia College Chicago as a Gates Millennium Scholar, where she received her BFA in Dance.

“I never thought about making dance a more viable [career] until Columbia, or being an instructor, but being there gave me the tools,” she says.

Sanders-Ward then attended New York University for her MFA, saying that she selected the school because it offered much of the same experience as Columbia but in a new city: “I liked the idea of being in a cultural mecca. Being in a city where dance was actively happening, where there was a dance community outside of the college.” She worked on various projects and festivals across the country before going to Senegal for a two-month preprofessional certificate program at Ecole De Sables, a dance center near Dakar.

From left to right: Marceia Scruggs, Chaniece Holmes, Vershawn Sanders-Ward, Destine Young, and Sara Ziglar rehearse in their Fuller Park space.

With Red Clay Dance, Sanders-Ward was able to blend the many styles she’d learned and loved through the years. She describes the work as “Afro-contemporary,” a fusion of Africanist movements and traditions that uses bodies to tell a story. The name “Red Clay” is borne of her own past and experiences as an African-American woman. Though she’s a native Chicagoan, she has family roots in Mobile, Alabama, where she used to visit her grandparents and play in the rich Southern mud. Connecting to the earth in turn connected her to her culture, and the idea for Red Clay Dance took its hold.

“As kids, when we play, we think, ‘What can we mold this earth and water into?’” Sanders-Ward says of Red Clay’s modus operandi. “It’s a layering of those two things: space and bodies, and history and culture.”

That methodology inspired her company members, Marceia Scruggs ’17, Chaniece Holmes, Destine Young ’13, and Sara Zigler ’10.

“I think [Sanders-Ward’s] willingness to have open communication with her artists is a strength for the individual and the collective,” says Zigler. “To work with Vershawn is to work collaboratively, is to test your limits, your vulnerability, face your frailty if you’re willing, and find resilience, patience in strength [and] in the process. Because she aims for her work and the work of the collective to be transformative, we are always the first to be transformed.”

The Merging of Two Companies

Transformation is the foundation of Red Clay Dance, and part of what makes the collaboration with the Keiga Dance Company an exciting next step in its evolution. With Byaruhanga, Sanders Ward has helped merge two cultures that share the same Africanist roots, and is working toward a collective goal of allowing its members to reflect on their past through bodily movement and freedom, while growing and changing the community around them.

The TransAtlantic Project came to life after Sanders-Ward met Byaruhuanga in Senegal after she completed her MFA. The experience was profound in a number of ways, outside of just that fateful meeting. There, she says, “all of the big things I was thinking about got their start.”

Destine Young will join the other TransAtlantic Project dancers on the Dance Center stage in November.

“It was an amazing experience in terms of opening my eyes as an American as to how I sit outside of this soil,” she says. “Being here in the States, I feel like my gender and my race are always very heightened. But being there, it was this feeling of being American first before those other things. I was grappling with that.”

Meeting Byaruhanga, a Ugandan, helped Sanders-Ward feel more comfortable; even though he lived in Africa, he was trained in East African dance, and struggled just as much with the West African style as she did. West African dance requires different kinds of rhythm; a dancer’s head and arms might move to a separate beat from their feet. The two forged a friendship that led to more collaboration efforts. Then, in 2010, they decided to merge their companies— Byaruhanga’s all male and Sanders-Ward’s all female—for one large communal performance, and spent the next seven years attaining funding to make it happen. The TransAtlantic Project was eventually made possible thanks to the MacArthur Foundation’s International Connections Fund, and has been in swing since last fall. The companies met twice more this year—in Uganda in May, and in Chicago in July—before their premiere performance in Chicago this November.

Rehearsing with New Friends

The first stages of Sanders-Ward and Byaruhanga’s cross-continental collaboration were done via Skype, where they chatted, shared images, and put together other inspirational ideas. The first physical stage of the project happened last October, when Red Clay traveled to Kampala, Uganda; that December, they all met in Chicago. The idea behind merging the groups was finding ways to blur the lines between their cultural and gender differences, and finding ways to control when those differences and similarities mattered. They—the four female performers in Red Clay and the four males in Keiga, all of them black—explored this through trust exercises and socializing over large meals. This community building helped establish a commonality.

“We [were] looking for them to excavate deep stories about their first movements and motions. Some of the stories that came out were really hard,” Sanders-Ward says of those initial meetings, stressing the importance of the trust exercises. “[It was about] getting them to a place where they knew enough about each other to reveal things.”

Chaniece Holmes rehearses in the Fuller Park fieldhouse.

After that trust was built, she and Byaruhanga worked on teaching the dancers “movement vocabulary.” They focused on improvisation, on the freedom of expression. Some days Byaruhanga led the rehearsals, some days Sanders-Ward did.

“It’s not both of us always in the creative mode,” she says. “We’ve been able to figure out this real collaboration. For me, it’s been great not to always be the producer. The dancers have also been able to give us so much. It’s been amazing to see how willing they’ve been to push each other, to be limitless.”

Red Clay company member, teaching artist, and activist Scruggs says she’s been profoundly changed by her experience with the TransAtlantic Project.

“Being graced with the opportunity to work alongside such sensitive-to-the-ear-and-spirit yet powerfully strong men, accompanied with four other gracefully beautiful yet mightily resilient women, is a dream that I believe the audience will not want to be awakened from either,” Scruggs says. “This experience—and just being in the presence of such genuine and welcoming spirits—has definitely welcomed serenity, gratitude, and a renewed acceptance of myself.”

The Next Steps

The two companies will present the culmination of their work at Columbia this November as part of the Dance Center’s 45th anniversary presenting series. Sanders-Ward was tight-lipped on what the performance will look like, but expressed that the audience will “see liberated and inhabited bodies in space with a suspension of limitation,” adding that the sets will incorporate Ugandan art—like masks and other props—sourced from the country.

“I feel like we’re removing what we assume black and brown bodies do and communicate and express,” she continues. “Hopefully you’ll see inhabited vocabulary that is just human, that is purely genuine, but also deeply rooted in culture. I hope that that’s what people will experience: this connection of culture, and reconnection of culture, that has been separated over time—and see how [those things] talk to each other and continue to influence each other.”

She hopes to continue collaborating with Byaruhanga in the future, and to eventually go on tour with both companies in the States, Europe, and Africa. As for presenting their work at her alma mater, Sanders-Ward says she feels grateful, noting that, as an alum, she talks about Columbia all the time. “It’s very fulfilling to be able to go to the places I have and to bring a project that’s so important to me back to a place that really fed me as an artist,” she says.